Order from us for quality, customized work in due time of your choice.

Abstracts

As the construction industry grows along with the economy, UAE construction companies are striving to succeed amidst steep competition to deliver projects by the required cost, meet deadlines, and provide high-quality work. The sector requires a motivated and robust workforce, effective and resilient project teams with flexible and supportive managers, along with a safe and healthy environment.

How will the UAE construction sector cope with the ever-increasing competition in the industry? Motivation and quality performance of teams could be the answer to this question. This study provided intensive research and a critical discussion on theories of motivation and the real situation in the UAE construction industry.

The research used qualitative and quantitative research; qualitative in the sense that the literature review involved a search of the vast databases of articles and journals on qualitative studies. The questionnaires were also qualitative and quantitative; quantitative in the sense that the participants were asked to rate from a five-point Likert scale on questions about motivation, performance, and job satisfaction, which also included open-ended questions on motivation and performance.

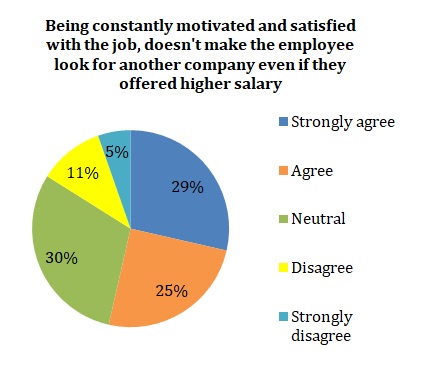

Managers and workers in the UAE are motivated by factors like work-life balance, the fulfillment of their basic needs, understanding of life’s situation, but only a few of the workers agreed on the importance of a high salary as a motivational factor.

Motivation involves tangible and intangible assets that act as a stimulant. Money can be a motivator, but there are other effective motivations like self-actualization which allows workers to aim high for the firm they are working for, and also self-motivation, and self-actualization, to name a few.

The main findings of the survey indicated that motivation influenced the participants’ work and money is not an ultimate motivator. The most important consequence of the work is that non-monetary motivators impacted most on both managers and workers.

Introduction

The rationale of the study

Motivation does not need to be overly used and introduced in the work environment. Many companies provide the best for their workers but a lot of them also fail as a business and as a manager. It may not be the motivation that can be seen as the real culprit but when workers fail to deliver what is expected of them, researchers tend to think that the workers were not made to think like the company thinks, or they were not motivated as successful people should.

What does motivation mean to the managers and people of the construction industry, the people who are always out there on the construction site? When the term construction is mentioned, it always refers to people who are building, workers who are mixed with the elements, so to speak. These are people who work hard and sweat under the heat of the sun, and who have to endure the harsh climate and weather. The answer to the question is motivation can do wonders, but how?

How can they be motivated to continuously work? Is high salary or money the ultimate motivational factor?

It might not be. Money can provide workers their needs, but there will always come a time that workers get fed up if managers are not able to provide what they need as humans. The workers might also reach a point that they have to give up. “We want money, but what we want you can’t afford,” they might say that; and then they leave the company and find other more fulfilling jobs. Expatriate workers might continue working for the company despite the disappointment and dissatisfaction they feel, but the desired performance is questionable.

Motivation should be identified and adequately applied to provide job satisfaction and eventually performance. The relation and the outcomes of motivation, job satisfaction, and performance have to be properly understood so that an efficient motivation environment can develop the needed worker satisfaction and performance (Doloi 2007, p. 30).

Many commentators opine that improvement and motivation should be constantly introduced to the workforce to ensure larger successes in construction projects. But workers are mostly ‘undervalued’ instead of regarding them as ‘the most important asset’ of the company (Vilasini & Neitzert 2012, p. 621).

This research will look at specific aspects of motivation, not motivation as a general term since motivation is a broad subject. This study will provide a description and critical analysis of the situation of the UAE construction industry and develop an understanding of whether the performance of the workers at the site increases by fulfilling their needs and motivating them. It is therefore a knowledge-enhancing activity for this Researcher and the students of the UAE for they will know the real situation in that sector of the economy, and how to improve the industry, the workplace environment, and the people who work for the industry. The aims of this research and survey were explained to the managers and firms that motivation was very important for project success and therefore the company success.

Participants in the research were asked about the importance of motivation, their opinion about motivational factors like incentives and bonuses about job satisfaction and performance, and the motivational factors instituted by the companies that made them love their job and work more for the company, and so on.

Aims

The aim is to provide an understanding of the relationship between motivation and performance among workers in the construction industry and whether motivation is significant to the attainment of quality performance of construction workers in the UAE.

Objectives

-

To understand whether employees are satisfied with their job in the construction industry in the UAE

-

To determine the relationship between motivation and workers’ performance

-

To establish a solid background on the motivational factors influencing construction workers and the importance of these factors by researching the latest published books, journals, and articles, and providing a critical analysis of the views and opinions of the authors

-

To evaluate the factors that motivate managers (Project Managers/Resident Engineers/construction managers/assistant resident engineers) and workers (project/site/junior engineers, foremen, laborers, storage keepers) at a site in UAE, and determine the demotivating ones

-

To determine and analyze the various motivational attributes introduced by construction companies in the UAE

Hypotheses

-

Hypothesis 1: Various motivational factors introduced by construction companies influence worker productivity and performance in the UAE.

-

Hypothesis 2: Managers at the site lack knowledge and skill in motivating workers and the positive effects of motivation.

-

Hypothesis 3: UAE construction companies have to implement incentive programs to motivate their employees and attain project success.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval is required of this survey research. In conducting the research, this Researcher asked for the guidance and approval of several companies whose workers and project managers became a part of the sample participants in the survey. Letter requests were sent to participants and the firms they were working for. The survey started only after the management and workers of the construction firms provided their written consent. High ethical standards were observed even in the formulation of the questionnaires and participants were made to understand the objectives and concepts of the research (Babbie 2004, p. 12).

Research Methodology

Phase 1: Literature Review

A literature review is used as a methodology to provide qualitative data from past researches. Literature was taken from the vast journals and articles on motivation and the state of worker productivity in the construction industry with a focus on construction companies in the UAE. Online databases provided many sources on workers’ motivation.

Phase 2: Collection & Data Analysis

Collection and data analysis included analyzing the vast information and data from the literature and the survey research conducted on a sample of workers and project managers from construction firms in the UAE.

This Researcher identified several construction companies and asked their workers and managers to participate in the survey. A part of the analysis centered on expatriate labor and how this type of labor is motivated since the UAE labor environment was dominated by expatriates (Al-Waqfi & Forstenlechner 2010, p. 365). Work environments in the construction industry were also defined and critically analyzed relative to workers’ motivation.

Phase 3: Conclusion & Report Writing

The conclusion is drawn from the critical analysis of the literature and the qualitative study from the survey of the participant.

Literature Review

Concepts, ideas, and outcomes of workers’ motivation in the UAE construction industry

Introduction

This chapter aims to define motivation and its relation and importance in work. There has always been a constant and intriguing question: Why do employees have to be motivated? And what kind of motivation has to be applied particularly in the harsh and demanding world in the construction industry? There are top managements who may not want to care about this word motivation simply because they have all the resources like high-salaries for employees, an effective IT infrastructure, and high-salaried middle-level managers who can do multi-tasks for them. But again, what can the middle-level managers do? What other managers can do to make their people work like they have to work for their own company or business?

Managements of the new millennium in this age of globalization and stiff competition in business know the value of motivation, that it is an important part of a company strategy. Without motivation, people will only work for the sake of earning money for their basic needs. This is the primary aim of this literature review, to dissect the meaning of motivation and how it has done for businesses and organizations, more specifically the construction industry, and how those organizations have applied it. Another primary aim is to know and critically analyze the qualitative studies conducted by experts in the field and compare this to the primary research in this present study.

Transforming workers into an effective workforce for any project is a challenge for construction and project managers. It requires skill, guts, and determination. Managers will always look to their workforce as their own once they see the performance, or quality performance, to say the least. But before that happens, they have to exert their valued time and effort to see outcomes. They have to know the motivation, the theories behind motivation and formulate a framework to make their strategies effective. That will mean outcomes by way of performance.

Motivating construction workers takes some tenacity on the part of the manager or project manager who must know their workers and what they want as individuals. The theories of motivation provide a single message, that for the managers to be effective, they must know the needs of their workers, particularly the current needs. However, many of the theories discussed in the literature do not have empirical studies to prove their effectiveness; thus, they remain as theories. But as commentators suggest, sometimes they are effective, sometimes not. Yet these theories continue to influence the minds of researchers and managers; the effectiveness of these theories depends on how they are applied.

What is motivation?

There are various definitions concerning objectives. Robbins (2001) defines motivation as ‘the processes that account for an individual’s intensity, direction, and persistence of effort toward attaining a goal’. Vallerand (2012) defines it as a hypothetical construct that refers to the factors that create the commencement, course, strength, and determination of behavior. These factors might be internally or externally motivated.

Motivation’s three main components can be focused on organizational goals. Intensity refers to how hard a worker tries to do his job. But high intensity does not necessarily lead to quality job performance unless it is focused on organizational goals. Quality of effort, i.e. effort that leads to quality performance, and intensity, must go together. The persistence dimension is also needed in motivation as it is ‘the measure of how long a person can maintain his or her effort’ (Robbins 2001, p. 156). Motivated workers can persist up to the time they will have attained their goals.

Robbins (2001) emphasized the organizational objectives in defining motivation, i.e. that motivated workers will focus their efforts and goals for the success of the organization. Motivated workers can have the intensity, direction, and persistence of effort to attain the organization’s objectives. On the other hand, Vallerand’s (2012) definition focuses on the worker’s behavior after motivation, i.e. the individual wants to start working and give all efforts, time and energy to attain the goals. Motivation changes the worker’s behavior. Robbins (2001) is concerned with the organization and the purpose of motivation is to change the behavior of the organization. A change in the employees’ behavior will affect their performance and organizational performance.

The purpose of motivation is quality performance. Performance indicators have to relate to the evolution of the project. Indicators can be expressed as a percentage, as a quantity or quality, or as a range. Indicators can have internal focus (for personnel and process-oriented) and external focus, which are customer and supplier oriented (Sussland 2000, p. 94). Sussland’s definition emphasizes quality performance as an outcome of motivation, or, motivation will result in outcomes. But he also emphasized indicators, for example, quality or quantity of work, i.e. before the worker was content with having a few things done, but now he/she wants to do a lot more and with quality.

Figure 1 demonstrates how motivation as a cycle works on an individual: first, he/she has the need; when this is met, there is gratification, and goal setting follows, but new needs soon emerge. This cycle relates to the individual needs; first, humans have needs for food, shelter, and clothing. But once these needs are met, the individual will worry about job or career, or attainment of prestige and power. As the figure shows, it is a vicious cycle.

Productivity and motivation complement each other, i.e. as shown in figure 2, the more motivated an individual the more he/she becomes productive (Warren as cited in Halepota, 2005, p. 15). But it can also be reversed as ‘increased productivity causes increased motivation’ and motivation depends upon productivity (Halepota, p. 15). Productivity may not mean quality product or outcome. The emphasis of Halepota’s definition is on the outcome, i.e. the individual will want to produce more, to attain further. The more the individual is motivated, the more he wants to achieve the goals; and the more he has produced, the motivation increases in intensity.

In Figure 2, motivation productivity is represented in the X-axis while productivity motivation is on the Y-axis. The diagram further demonstrates that as motivation increases, so does productivity. They extend from Y1 to Y3 and X1 to X3, respectively.

Importance and effects of motivation on the construction industry

Managers in construction firms are faced with the question of how to encourage workers to exert energy in innovative activities and how to sustain this process for a long time. Motivation encourages workers but managers have to determine the effective motivation applicable to workers and the kind of situation.

Construction companies have to motivate workers, along with their teams, to acquire the best results, quality performance, loyalty, and trust. Companies invest in their workforce to reduce turnover and acquire more customers. They also use various motivational factors to achieve organizational performance (Thwala & Monese 2012, p. 633).

Construction work utilizes project teams to handle small and large construction projects in various workplace environments. Project managers and workers endure the physical, emotional, and climate stresses involved in their jobs; and managements have to be flexible in employment and working conditions and arrangements.

The real situation in the field may not be felt by an ordinary researcher or author. Researchers and research teams have to go and feel the situation, particularly in construction sites in the UAE or in Dubai where a lot of construction work never ceases. People there endure the heat and the tiresome environment. This is a fact that needs to be investigated because it relates to motivation. In construction, people have to be motivated to attain quality results.

Workers in construction should be dynamic to acquire results, but in being dynamic they should be watchful to avoid mistakes. Construction companies use teamwork, problem-solving teams, and multi-tasking groups, to maximize the role of workers in decision-making. Various motivational factors have to be used in this process of team building. In motivating workers, managers utilize their utmost discretionary power to achieve quality performance (Berg 1999, p. 113).

Berg (1999) emphasized the importance of teams in the discussion. Construction work is about teams and projects. It has been said that a construction project is composed of many projects worked out by project teams that are under sub-contract. Sub-contract teams have their own ‘motivation needs’.

The UAE Construction Industry

Like any other construction industry, UAE is labor-intensive, composed of various projects implemented by teams, contractors and sub-contractors, and regular and casual workers. The diversity of the industry is paramount; it includes skilled and unskilled, managerial, professional, clerical, and administrative jobs. The project-based scope of the construction provides vast challenges to the management and the people in the industry. Multi-cultural teams, formed and managed for a short period, operating under stringent cost constraints, are expected to work for one project and complete it without hesitation.

The latest statistics reveal that UAE has a population of approximately four million, but nationals account for only 17% of the total population. From this population, the country has a small labor force, considering that only 40 percent of the population is believed qualified to hold a managerial job, aside from the fact that most men have their businesses. Thus, UAE nationals comprise a small segment of the labor force (Behery 2011, p. 22).

Described in Behery’s (2011) article is the situation in the UAE, that projects were composed of UAE nationals and expatriates, or workers who hailed from other parts of Asia. This kind of workforce has to be motivated to deliver quality performance. But it was also emphasized that without motivation expatriates will always deliver what is expected of them. The only question is what kind of performance they will be able to produce. There might be a different kind of motivation, for example, a punitive one, like when the manager terminates the contract because the contract worker is not delivering quality service; or the manager might provide rewards as motivation. These assumptions will be dealt with in the primary research for this study.

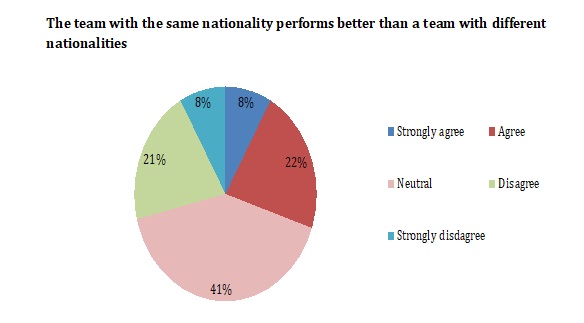

The UAE construction industry is reliant on migrant workers who come from different countries in Asia. The nationality or nationalities that complement the other members of the labor force are mostly Asian, European, and American who are holding managerial jobs. However, managers and scholars consider diversity in the workplace as a positive factor as it increases competency in the workforce, at the same time it enhances the good relationship with diverse communities (Alserhan, Forstenlechner, & Al-Nakeeb 2010, p. 43). In Alserhan et al.’s (2010) research analysis, having a workforce of various nationalities did not affect their performance. This opinion will be examined in the primary research for this study, with the question in one of the questionnaires: does having a team composed of different nationalities affect performance in the job?

During these recent years, the government has shown interest in the development of its workforce; there is the recent drive on the Emiratization of the workforce, meaning, the government wants nationals to dominate the workforce. However, the UAE “market economy” has been developed, attracting skilled and professional employees. Globalization and technology have developed and provided managers in the UAE with new tools and knowledge on HR practices (Forrest, 2004; Morada, 2002 as cited in Behery, 2011, p. 22).

There are a variety of factors and determinants of job satisfaction particularly in the UAE context where it is supposed that expatriates have to endure the weather and climate which is different from their country of origin. It is important to describe the environmental factors construction workers deal with, such as the climate and weather in the UAE as this influences the workers’ will and perseverance in carrying out their job and even their relationships with their managers and co-employees (Abdullah, Djebarni, & Mellahi 2011, p. 126).

UAE has a very hot summer that seems unendurable for non-national workers who come from a different environment. In a study focusing on the hydration status of workers, it was found that workers had to maintain their body fluid levels to endure the hot environment and maintain their performance and productivity in the workplace. The study recommended good hydration before workers start their job (Bates & Schneider 2008, p. 5). The work environment in the UAE may not be different from other work environments where the expatriates came from because Asia’s climate and the weather are not different from the UAE.

Managers’ core competencies

Engineering managers’ perception of their job and skill competencies has been the subject of a study involving engineering managers (EM) in the UAE. The study aimed to measure the performances of construction managers and to develop EM competency “domains”. This kind of manager has a multi-faceted job, e.g. technical and managerial competencies, so that their core competencies are of special interest for top management. Competencies refer to the standard or quality of the manager’s performance and his/her characteristic traits (Hoffman, 1999 as cited in El-Baz & El-Sayegh, 2010, p. 3).

Construction companies that adopt a competency-based method in determining employee performance usually develop a competency model. This is a set of competencies grouped following organizational performance objectives. Employees have to understand what they need to work to achieve those goals. This is also a significant HR objective for construction companies in the UAE. By measuring their performances against the performance standards set by the company, they can be improved and motivated accordingly. Construction companies doing this are concerned about workers’ motivation by way of building upon their managers, particularly project managers. By increasing the capabilities of their managers, they can motivate their workers.

A construction company is composed of engineering managers and project managers; thus, engineering managers should know system engineering to recognize the need for system support in organizational development. As the EM improves in his/her work, he/she is expected to do important strategic planning that may include important aspects in technology, product, and product development (El-Baz & El-Sayegh 2010, p. 5).

The study interviewed academicians and engineering managers who were working from oil and gas, manufacturing, utility, and construction sectors from the UAE. EMs usually work in cross-functional teams and are competent in technical skills. The study used the AHP method to determine the significance of the competencies concerning the model as felt by the participants in the UAE. The AHP is a method to help in decision making and in dealing with difficult decisions.

It was found in the study that, among the three competency models, the “People” domain became the dominant domain, followed by the “Business” domain, and then the “Environment” domain. This showed that engineering managers preferred interpersonal and leadership competencies. Construction companies in the UAE are placing much importance on leadership training and EMs would like to cultivate their leadership traits to meet their organizational goals. In the “Interpersonal” sub-domain, EMs put much importance on effective communication, and on “Leadership,” they put much weight on vision and strategic thinking. EMs are more concerned about employees’ behavior than top management.

Cross-cultural sensitivity and awareness of worldwide issues did not have the interest of the EMs. They emphasized that they did not have to accommodate a multi-culture workforce because they felt that this is the job of top management.

Workers’ motivation in construction projects

Construction projects demand specialized teams with the skills, abilities, experience, and knowledge needed for the completion of the project. Workers that compose these teams must be especially motivated (Chen et al. 2012, p. 783). Without motivation from project managers, unexpected problems might come up. The top management has to emphasize coordination and communication. This is so because of the increased competition and the large-scale projects introduced due to globalization. Firms have provided alternative management tools to be able to quickly respond to complex situations in the field (Chen et al., p. 783). While other authors emphasized that motivation must be applied to construction workers, Chen et al.’s (2012) research suggested that it is already a part of construction work, i.e. that construction projects cannot fully function without motivation and that it is a necessity in construction sites. This is a different opinion from the other authors. This Researcher thinks that motivation is already a part of construction projects. The UAE contractors and managers already know the importance of motivation and that they have applied it to all of their projects. Managers and workers also know how to apply and attain motivation.

Various organizations have promoted HRM practices to enhance employee performance. Motivational factors should include training, higher salaries, promotions, team building, and empowerment. These factors are believed drivers that enhance satisfaction and influence employee performance and concern for the firm. But motivation does not necessarily attain immediate results. Some managers work hard to achieve motivational outcomes like spending quality time with employees, providing advice to workers, and even extending help to solve personal problems (Saleem, Mahmood, & Mahmood 2010, p. 214).

Firms have used different approaches to attain job satisfaction of workers and motivation is only one of these practices. Job satisfaction can lead to higher productivity, loyalty to the organization, reduced absence, and higher organizational success (Abdullah, Djebarni, & Mellahi 2011, p. 127). Some studies found that the involvement of workers in the workplace creates job satisfaction and may lead to worker performance and organizational performance. This is the hypothesis in some researches and contention by many managers in the UAE (Behery 2011, p. 21).

What motivates workers and project managers in the UAE?

This topic can be understood with another thought in mind: Is there a different kind of motivation for the workers and project managers in the UAE? Every kind of work environment needs a different motivation, but the motivational factors will be discussed in the next chapter on theories and motivation and the analysis of the results of the primary research conducted on the workers and managers of the UAE construction companies.

Construction work is a physically demanding job resulting in lower productivity and motivation that may lead to poor performance, negative job satisfaction, and eventually accidents (Abdelhamid & Everett 2002, p. 427). This means construction workers need more than just economic motivation as safety and health are of paramount importance.

In the days of Frederick Taylor (as cited in Abdelhamid & Everett, 2002), during the early 1900s, this father of scientific management argued that management must meet the needs of workers using providing a conducive and safe workplace and an environment that reduces fatigue so that workers can work effectively and perform a quality job. Eliminating or minimizing physical fatigue in the workplace enhances workers’ health and safety and thus they can provide quality work (Abdelhamid & Everett, p. 427). Workplace situations can predict job satisfaction better than other motivational factors (Abdulla, Djebarni, &Mellahi 2011, p. 140). This is precisely what is needed in the UAE context, that while project teams are composed of workers from different nationalities they have to be provided with a healthy, safe, and conducive work environment. The work environment alone may be ‘demotivating’ to workers which will affect their performance. The managers and companies know this for sure. Demotivating factors are discussed in one of the questions in the primary research for managers and workers.

There have been many studies conducted on the physical demands in the construction industry that were based on the workers’ physical capabilities and energy expenditures (Christensen 1953; Lehmann 1961; Astrand 1967; Durnin and Passmore 1967; Astrand et al. 1968; Hansson 1968, as cited in Abdelhamid& Everett, 2002). The studies were focused on young healthy individuals, as construction activities require young males who have the physical strength to do the extremely physically demanding job. The studies had a common conclusion, which was that assessing physiological demands in construction was difficult.

Workers should not be working in “caves” which limit interaction and flexibility among workers. Organizations should provide flexibility and collaboration among employees by removing physical barriers in the workplace such as high walls, closed offices, and doors. Offices are now composed of cubes but there are instances that private offices are also needed for employees who need closed and deep concentration in their jobs.

Is money a motivating factor in workers’ performance?

This is one of the primary objectives for the research, whether monetary factors can motivate workers or whether it can overpower the non-monetary rewards as motivation. Without looking into the vast amount of journals and articles on motivation and money as a motivating factor, the question above can be answered loudly. Yes, money is a motivating factor. For many people out there, for those living in situations with the least resources and whose basic needs are not easily met, money is indeed a motivating factor.

The question is will it last? Or, does motivation through money translate into a good job or good performance with quality results and at the shortest possible time? Will, the worker loves his/her job for the sake of money? These are questions that need answers.

In an ordinary office environment, variable pay to achieve high performance may weaken employees’ response to a stimulus, or a bonus type of motivation can allow employees to get distracted to achieve the company’s goals (Osterloh & Frey 2002, p. 107). Firms have tried to provide payment and to achieve performance, for example, managers are given stock options and several forms of bonuses. In some countries, employees in the public sector are compensated following their performance. This particular type of motivation is known as extrinsic motivation where employees are given incentives. But mere money as compensation for what has been done is not enough to achieve the performance required of the employee (Osterloh& Frey 2002, p. 107).

Employees are not motivated by money all the time. There are innovative non-monetary rewards like paid vacations, time off from work, favored parking, or gift certificates that can be quite effective in encouraging employees (Bragg, 2000; Geller, 1991 as cited in Govindarajulu & Daily, 2004, p. 368). Some workers may be more motivated by recognition and praise than monetary rewards.

A study was conducted which found that workers would do their best if their job were recognized (Jeffries, 1997 as cited in Govindarajulu & Daily, p. 368). It was found in the study that motivated workers were workers who participated in decision making; they performed well and provided quality jobs than workers who were not motivated.

Ramus (2001 as cited in Govindarajulu & Daily) provided empirical evidence showing that supervisory technique that encouraged daily praise and environmental awards was considered the top motivational factor for environmental creativity and problem solving by employees. Studies in Dutch businesses showed that recognition awards for innovative ideas regarding environmental improvements motivated managers and employees.

Studies on motivation

Is another question relative to the topic is: Do the salary and allowances of workers and managers motivate them? In this age of high-stakes living, employees expect high salary and allowances, nobody will work for a low-salary that is not commensurate to their qualifications and will not meet their basic needs. Employees who acquired high education (Ph.D., Master’s, etc.) will not accept a meager salary. In the initial months, they may accept it but while they grow with the company, they always want higher compensation. Employers consider this as part of their operating costs and they expect much from their managers and workers. Belcher and Atchison (1987 as cited in Ghazanfar et al., 2011) emphasized the importance of high compensation for employees so that they perform better and deliver quality work. Evidence was provided in the study of Ghazanfar et al. (2011) that employees are satisfied with high salary and this allows them to perform better. An important part of this present study is embodied in one of the questions: Are workers regard high salary as a motivating factor? The work of Ghazanfar et al. (2011) proved this in their primary research. This Researcher poses the question: Can this be true with the workers in the UAE?

Recent management efforts have been focused on providing effective strategies that will result in organizational performance. Researchers aimed their investigations on the relationship of employees’ attitudes and behavior with their performance. This gave them the impetus to focus on job performance and turnover (Locke, 1976 as cited in Irshad & Naz, 2011). Some researchers like Mowday, Porter, and Steers (1982 as cited in Irshad & Naz, 2011) aimed their investigation on organizational commitment as a relevant predictor of employee behavior. If top management is committed, employees tend to do better.

Theories of Motivation

Theories of Motivation

This chapter will focus on theories of motivation and an analysis of the theories. As said in the literature review, theories of motivation have remained as theories because there have been no empirical studies to support the theories. All the literature has been assumed motivational factors that tend to support or provide evidence for the theories. Also said earlier, there are times they are effective and some other times they are not. The purpose of citing these theories is to know how they relate to motivation in the UAE construction industry. There might be some instances that these theories apply to the UAE context, or they may have been already applied in this regard. This can be verified during the comparison and analysis of the results of the survey.

Content Theories

Content theories focus on internally-motivated theories or internal drives that motivate behavior or stimulate individuals ‘to act or move’ (Ghazi et al. 2010, p. 94). The following are important content theories.

Maslow’s theory

Maslow’s theory explains the way human behavior reacts and the theory helps us understand what strategies to use to motivate people. The theory classifies the different needs, arranged in a ladder or pyramid, wherein the needs situated at the bottom of the pyramid have to be met first before the upper needs in the next steps of the pyramid can be met. Physiological needs (e.g. hunger, thirst, shelter, etc.) have to come first before safety, social, esteem, and self-actualization. Self-actualization stimulates what one wants to become and this includes ‘growth, achieving one’s potential, and self-fulfillment’ (Robbins 2001, p. 156).

Maslow’s theory is not only popular, but it has also been applied in many philosophies and principles, albeit with no studies to support it. Hagerty (1999) that Maslow’s theory used to be the reason why China insists on its communist ideology than democracy. He says that before democracy can be implemented in China, it must first meet the basic needs of the people. And that may still far on the horizon, considering that it has more than a billion people to feed. Maslow’s theory can be referred to as the quality of life of a population.

Even if the researcher cannot find any empirical study to support Maslow’s theory, he finds that this is the most logical of all the theories. In the literature on motivation, one can only find motivational factors and the needs that people must meet. But many studies have regarded Maslow’s theory as very logical and that requires good thinking. Robbins’ (2001) analysis of Maslow’s theory always tends to focus on the organization and what motivated people do for the organization. The behavior of the organization is the outcome of the behavior of the employees.

In determining the needs of workers, the manager must understand what level of the hierarchy the workers are currently on and focus on satisfying those needs at or above that level of the hierarchy. Different factors motivate people and people are motivated according to their current needs. Understanding the needs of workers helps managers what motivating factors to use in the workplace. By using this knowledge, managers can provide meaningful rewards for workers’ performance.

Maslow classified the needs into higher and lower needs. Physiological and safety needs belong to the lower-order needs, while the higher-order needs have the social, esteem, and self-actualization needs. The difference between these two needs is that higher-order needs are internal-satisfaction needs, and the lower-order needs are the external satisfaction needs (for example, pay, union contracts, and tenure). According to Maslow, in times of great abundance, all workers of permanent status have their lower-order needs already satisfied by management (Robbins 2001, p. 157).

Maslow’s theory is the most popular because of the way he deals with his theory. First, he focused on the Freudian concept, clinical psychology, and later he explained that man needs a stimulus to trigger the inside which is lacking control. But the lacking dimension is that Maslow did not provide empirical substantiation to his theory; thus it has remained a theory and the logic for which it was framed cannot support the hypothesis: ‘that unsatisfied needs motivate, or that a satisfied need activates movement to a new level’ (Robbins 2001, p. 157). But also in recent years, Maslow’s theory of self-actualization has been under attack, i.e. it is too vague to be understood by a student or ordinary researcher. The criticism arose from Maslow’s lack of scientific knowledge in his theory. But Maslow just reacted to the way clinical psychology figured how an ordinary human being becomes happy and contented in life. Clinical psychology’s concept of human behavior first started with the Freudian concept of psychology that man naturally responds to stimuli.

The last ‘phase’ in Maslow’s theory, self-actualization, provides a different perspective from the previous ‘phases’. The previous needs in the hierarchy are triggering mechanisms to reduce a particular defect in the individual. Man needs to exercise control in this respect because of the deficiency. It can be done when the individual changes or has to grow as a human being.

McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y

There are two important and different views for human beings, according to Douglas McGregor, one that is negative, known as Theory X, and the other one which is positive, known as Theory Y. McGregor studied human behavior and one of his important findings was that a manager’s view of the nature of human beings is based on a certain grouping of assumptions and that he or she tends to mold his or her behavior toward employees according to these assumptions’ (Robbins 2001, p. 157).

McGregor’s findings state that Theory X workers naturally do not like work and will do all things to avoid it. Thus, employees have to be forced, controlled, or threatened with punishment, to accomplish something. Employees avoid and dislike responsibilities and look for formal direction as much as possible.

In contrast to Theory X is the Theory Y model nature of human beings wherein McGregor assumed that: workers look at work ‘as natural as rest or play’; workers are motivated to have direction and self-control as long as they commit certain goals; an ordinary worker/employee can learn to accept and hold on to responsibility; and, anybody, any worker/employee, can provide good and innovative decisions for the company or project being undertaken (Robbins 2001, p. 157).

Some researchers have combined Maslow’s needs theory and McGregor’s assumptions. Theory X assumes that human nature seeks first lower-order needs; thus, they dominate individuals. Theory Y is for higher-order needs as dominant. McGregor concluded that Theory Y is more valid than the other theory, and so he proposed the participative decision-making process for firms and projects. Employee job motivation, according to this theory, proposes responsible and challenging jobs, and good relations with managers and co-workers. According to Robbins (2001), there has been no valid evidence to support these theories and that both theories can sometimes be effective, depending on the situation. There might be a slight difference between the two theories concerning McGregor’s Theory Y and Maslow’s basic needs theory but they all point to employee job motivation and the good relation of the employer and employee.

Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory

Frederick Herzberg believed that anyone can improve in job performance but that the employees’ relation to work and attitude can determine success or failure in the job. Herzberg investigated workers’ attitudes to their job, or what people wanted of their job. The focus of his investigation was on employees’ description of their situations wherein they felt ‘exceptionally good or bad about their jobs’ (Robbins 2001, p. 158). The results of this investigation were tabulated and categorized.

From the categorized responses, Herzberg concluded that the situations wherein employees felt good about their jobs were different from those when they felt bad about their jobs. Some characteristics were related to job satisfaction while others to job dissatisfaction. According to Herzberg’s investigation, intrinsic factors were related to job satisfaction and this included work, responsibility, and achievement. On the other hand, job dissatisfaction was related to extrinsic factors, like ‘supervision, pay, company policies, and working conditions’ (Robbins 2001, p. 158).

McClelland’s Theory

McClelland’s theories have been linked to achievement, power, and affiliation motives. The achievement, power, and affiliation motives are somewhat similar to Maslow’s theories on self-actualization, esteem, and love needs. The intensity of the motives varies on individual workers and depends on the kind of occupation.

The power motive causes a person to have control, influence, or impact on another individual or group (Winter, 1973 as cited in Schmidt & Frieze, 1997, p. 425). Individuals of this type will have satisfied needs through leadership roles or by having careers as an executive, professor, psychologies, priest or pastor, as this kind would like to have direct, rightful, interpersonal power over people (Winter & Stewart, 1978 as cited in Schmidt & Frieze, 1997, p. 426). People use products as a way of showing power.

Process theories

Process or cognitive theories are mostly focused on ‘conscious human decision processes’ as examples of motivation. These theories focus on how human behavior is strengthened, directed, and preserved (Ghazi et al. 2010, p. 94).

Expectancy theories

Several theorists have formulated and written about the expectancy theory. This theory focuses on relationships based on effort, performance, and rewards. The most popular of this type is Vroom’s expectancy theory.

Vroom’s expectancy theory

Vroom developed two models to describe the expectancy theory. The first one is the valence model which captures the ‘attractiveness, or valence, of an outcome by aggregating the attractiveness of all associated resultant outcomes’ (Geiger & Cooper 1996, p. 114). The valence model, if applied to a student’s assessment, states that a person gets attracted to the course grade. The second expectancy theory is the force model which is demonstrated in the student’s motivation to succeed as he/she is attracted by academic success.

The expectancy theory examines motivation on the concept that people’s actions follow a certain path of action. This theory can be very applicable to the construction industry in which the motivation depends on the workers’ response to the reward and whether doing more good job will lead to that reward. But the motivation for construction workers cannot be simply understood via the expectancy theory.

The motivational pattern for construction workers must be provided with a unique set which is a combination of ‘Vroom’s expectancy theory, Maslow’s needs theory, Adam’s equity theory, and Skinner’s reinforcement theory’ (Hewage & Ruwanpura 2006, p. 1076). The expectancy model prevails over all the others when speaking of the social cognitive theories of motivation. Achievement goals are related to individuals’ expectations.

Workers can be motivated as a team since teamwork is important in construction success. Understanding cultural factors and individual weaknesses can provide strength for the team and improve performance.

Goal-Setting theory

Setting goals influence human motivation and behavior. The goal-setting theory, formulated by Locke and Latham (1990 as cited in Latham, 2001), states that: 1) specific high goals can motivate and result in higher performance than setting no goals at all; 2) the more difficult the goal, the higher the performance; 3) feedback, involving oneself in decision making, and competition can lead to performance since these motivate goal setting; 4) direction, effort, and persistence, which are mediators of goal setting, are motivational. Commitment is important in goal setting. Locke provided empirical studies as evidence for this theory in his doctoral requirement and laboratory experiments.

Goal setting is one of those strategies that firms have considered to manage factors that cause stress in the job, particularly task or role demands. While some particular jobs are more stressful than others, individuals differ in their ability to respond to stressful situations. Individuals perform better when they are challenged by certain goals and when they receive comments or feedback regarding their good performance.

Using goals can reduce stress and motivate workers to work harder and set goals for themselves. Robbins further states: ‘Specific goals that are perceived as attainable clarify performance expectations. Additionally, goal feedback reduces uncertainties as to actual job performance. The result is less employee frustration, role ambiguity, and stress’ (Robbins 2001, p. 571).

Equity theory

The construction business is filled with disputes; thus, stakeholders devised ways to avoid this. Negotiation is a skill needed by managers but many of them do not know this art. In the construction industry, there is the traditionally adversarial relationship between clients and contractors, considered a major source of disputes and litigations at times (Cheung et al. 2003; Al-Momani 2000; Cheung and Lieu 1995; Jannadia et al. 2000; Cheung and Yiu 2006, as cited in Yiu, Keung, & Wong, 2011, p. 40).

Reinforcement theory

This is also known as ‘Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory’ which states that individual workers are motivated by rewards and punishment. Reinforcement uses rewards or penalties to attain behavior outcomes. Operant behavior is the result of rewards. The theory postulates the concept of approach and avoidance, with emphasis on rewards and punishment as motivational factors (Gray 1973 as cited in Smillie, 2008, p. 360). Reinforcement sensitivity can be measured through a psychological measurement known as psychometric using questionnaires. Reinforcement theory is more of external motivation than the internal drive.

Motivation may be in the form of incentives or disincentives (I/D). The logic behind this method is that incentives can cause early completion and disincentive as a form of penalty for late completion. These motivational factors drive contractors to perform at the same time as project managers motivate their workers to do the same. (Shr & Chen 2004, p. 84)

Incentive/disincentive projects are mostly applied to highway construction wherein a government agency responsible for such a project is constrained to complete the highway construction to avoid disruption of highway traffic and other services

Extrinsic and Intrinsic motivation

Extrinsic and intrinsic are outcomes of motivation. Osterloh and Frey (2002) have cited instances wherein monetary consideration can reduce performance. For example, some work can be considered by an employee as having social relevance and when this is accompanied by money, the values or norms can be disregarded. Good management cannot be matched by money as a motivational factor. To fully depend on money as an incentive cannot motivate complex tasks. Intrinsic motivation is characteristic of good management which can be attained through forming a strong personal bond among managers and employees by recognizing a good job of appreciating the good deeds the employees have done for the project or the company.

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations combine to provide ‘the highest level of motivation’ (Vallerand 2012, p. 42). But in a study conducted by Deci (1971 as cited in Vallerand, p. 42), it was found that motivating individuals to work on something to receive a monetary reward (which is extrinsic) ‘produced a decrease of subsequent intrinsic motivation in the activity’ (Vallerand, p. 43). This experiment proved that intrinsic motivation was weakened by the controlling power of reward. Intrinsically motivated workers act to satisfy their need for independence, work because they want to work, and enjoy and feel the pleasure out of those activities (Shin & Kelly 2013, p. 143).

Vocational identity refers to people’s ability to discover, plan, and formulate goals for themselves (Shin & Kelly, p. 143). Intrinsic behavior comes out when individuals feel that the job is challenging and rewarding (Bruno 2013, p. 136). Deci and Ryan (1985 as cited in Kapikiran, 2012) explained it as ‘internal target behavior instead of external factors’ (p. 705). Extrinsic motivation refers to engaging in tasks because of rewards that are not related to the tasks (Deci& Ryan, 1985 as cited in Moneta, 2012, p. 491).

The question is whether economic incentives induce the needed performance. Some commentators opine that it can lead to unexpected results (Bruno 2013, p. 137). According to theorists, extrinsic and intrinsic motivations have different meanings in the economic and psychological perspectives. Psychologists talk about the ‘evolution’ of the individual in doing the job because of the rewarding activity, while economists look for ‘the effect on behavior (and performance) of a reward supplied in a previously nonmonetary relationship’ (Bruno 2013, p. 137).

Vroom’s expectancy theory is based on the probability that a worker’s action can expect an outcome. The concept of outcome expectancy is ‘the belief that performance will be followed by the desired outcome’ (Hewage&Ruwanpura 2006, p. 1076).

Research Design and Methodology

Introduction

In construction sites, workers have to meet many demands and experience pressure to the point that they lose interest in their job and in providing quality performance. Construction managers and project managers have to motivate workers into producing the quality of work they want for the project on hand. The point of this study is to assess and understand whether motivation can stimulate the quality performance of workers in construction projects.

A performance measurement system is a set of metrics used to quantify both the efficiency and effectiveness of actions’ (Rezaei, Celik, & Baalousha 2011, p. 743). Performance measurement helps to bring more scientific analysis into a decision-making process. It underlines the change towards management by information and knowledge, instead of primarily relying on experiences and judgment (Rezaei, Celik, & Baalousha 2011, p. 743). The factors affecting performance measurement are based on one, or a combination of some criteria like finance, operations, quality, safety, personnel, and customer satisfaction. Ho (as cited in Rezaei, Celik, & Baalousha 2011, p. 743) defined performance as the achievements in quality and quantity of an individual or group work.

The objectives of this study were to determine the relationship between motivation and performance in construction sites by way of questionnaire surveys on workers and project managers in construction companies in the UAE. The background studies for this work are the literature review conducted on qualitative studies of past researches; and the questionnaire interviews on workers and managers who were classified in the questionnaires into four classifications, namely: 1) project manager/resident engineer/ projects control; 2) construction manager/ assistant resident engineer/project coordinator; 3) project engineer/site engineer/site inspector/planning engineer/ junior engineer; and, 4) foreman/surveyor/safety engineer/laborer/driver/storage keeper. These four types of workers in construction sites were the participants in the survey in different construction projects across the UAE.

Rosén, Andersson, and Åteg (2005) introduced the concept “Moveit-effect,” which implies that different methods aimed at workplace improvements sometimes also have the side effect that the employees involved will become more motivated to actively take part in the improvement activities. There is a need for a method ‘to monitor employee motivation in order to develop methods with such an effect on motivation’ (Hedlund et al. 2010, p. 148).

The UAE, the chosen survey site

The UAE became a federation of Trucial states in 1971 wherein many thought it was just a big field of deserts needing help from the international community. But there were many optimists, particularly the educated elite, who thought modernization for the UAE was paramount for its advancement in the new millennium. Oil was the answer. When black gold came into existence, the UAE was going full speed (Heard-Bey 2005, p. 358).

Since construction companies are instrumental to economic growth, by far they are the most widely seen and one of the most important sectors in the UAE economy today. Many problems have arisen in the sector; to deal with the problems of the organizations and the people running the organizations is a major part of this paper.

This research has chosen the UAE and the construction companies that are instrumental to the rapid growth of the member states. This federation of smaller states is unique in its structure and the application of planning and development. Take for example Dubai, which has gained worldwide popularity because of the way it handles economic development like an experienced businessman. Oil production is beginning to decline but the desert has been turned into a big real estate business. Dubai is now home to regional headquarters of worldwide organizations; the desert has been converted into offices, apartments, and several clusters of high rise buildings with ‘free zones’ for villas for the rich and famous.

The UAE construction industry is in an unmatched stature these past few years. The country used petrodollars to jumpstart its economy and stimulate rapid growth and meet the people’s demand for shelter, offices, electricity, government buildings, and many more activities for progress and economic development. The economic boom started in the mid-1990s when the country shifted from an oil-dependent economy to a more industrial, commercial, and tourism hub in the Middle East. The public and private sectors have collaborated behind this growth.

The Emirate of Dubai is now considered to have the highest per square kilometer of construction activity globally. Recent statistics showed that of the $50 billion Gulf-wide construction spend, approximately 60% of it, $30 billion, is attributed to the UAE alone wherein a big share is in Dubai (ITP Construction 2004 as cited in Faridi & El-Sayegh, 2006, p. 1167). The population of Dubai will rise several times because of the influx of businessmen and people from different parts of the world. Sharjah is now home to international universities. Fujairah has taken advantage of its geographical location as it becomes a shipping destination giving Middle East countries access to the Indian Ocean.

The UAE has a significant role to play within the global community of nations. Dubai is one of the ‘world’s trading centers offering a gateway to a market of more than one billion people’ (Connell, Burgess, & Hannif 2008, p. 67). Because of this scenario, much emphasis by construction firms has been focused on problems in the industry, especially on the delays or the specified project duration due to the present trend of making projects having a fast track approach. Causes of delay have to be monitored during the entire course of the project to complete the project on time. Of note are two of the major causes of delay which are the productivity of the workforce and experience and supervision of the project managers of construction projects. It was also noted that all the players involved in a construction project were responsible for their respective roles at the different stages of the project. (Faridi & El-Sayegh, 2006, p. 1167)

Methodology

The survey forms were distributed to the various construction companies, but only to 200 prospective participants of 10 construction companies in different parts of the UAE, wherein 96 (21 managers and 75 workers who were performing various functions) responded positively to the survey, making the response rate to 48%. ‘Responding positively’ means that the sample received the questionnaires, and after a few days they sent back the questionnaires through emails, along with their corresponding responses. The sample was chosen at random from 10 companies actively operating in the UAE.

The UAE has 16,000 contractors but this Researcher had limited access to only a few since it was very difficult to obtain and cope with the time and attention of the contractors for this survey. From this number, only about 12,000 are active, which is composed of large, small, and specialty contractors. The sample chosen for this survey were working for large and medium-size general construction contractors. There were 12 project managers (or resident engineer, project controls); 9 construction managers (or assistant resident engineer/project coordinator); 40 project engineers (or site engineer/inspector, planning engineer, or junior engineer); and 35 foremen (or surveyor, safety engineer, laborer, driver, storage keeper).

This section will illustrate the questions concerning each skill and category that have been included in the survey.

The qualitative evaluation was faced with the following issues:

-

Q1 – Age demographic

-

Q2 – Years of experience with the construction industry

-

Q3 – Educational level of participants

-

Q4 – Functions and duties of participants in the companies

-

Q5 – Motivation of employees

-

Q6 – Motivating factors from which participants were to grade

-

Q7 – Performance of workers, containing 7 performance outcomes

-

Q8 – Motivating factors used by managers, containing 6 factors

-

Q9 – Motivation for project engineers, site engineers, or foremen, surveyor

-

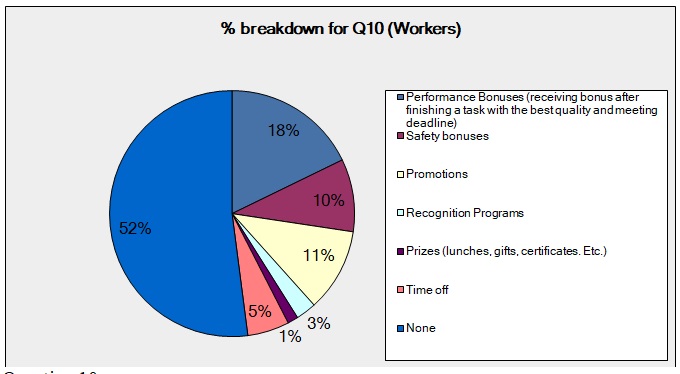

Q10 – Incentives for workers, containing 8 factors

-

Q11 – Demotivating factors

-

Q12 – Comments/suggestions from participants

-

The questionnaire

Table 1. demonstrates the different categories of questions.

Questionnaire objectives

The purpose is to evaluate and understand the relationship between motivation and performance in construction sites.

Age demographic

Table 3. Age Answer Options.

Years of experience in the construction industry

Educational attainment

Table 4. Educational Level Answer Options.

Occupations/Functions in the company

“In order to investigate the occupation of the participant and differentiate the answers from both categories as option 1&2 are considered managers since they have the final decision in different aspects, and 3&4 are considered workers since they follow the instructions from their managers”

Table 5. Occupations Answer Options.

Motivation and job satisfaction

Table 6. Motivation and Job Satisfaction Answer Options.

Importance of Motivational factors (Objective 6)

“To understand/Rank the main factors that motivate the site employees in UAE the most, citing the most and the least motivating factor”

Table 7. Motivational Factors’ Importance Answer Options.

Relation between motivation and performance

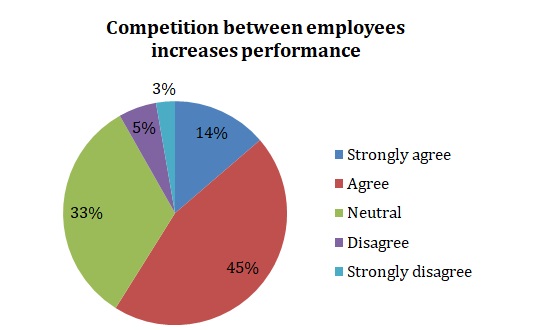

“To evaluate the relation between motivation factors such as environment, nationality, trust and competition, and on performance whether it will increase after the workers are motivated”

Table 8. Relation between Motivation and performance.

Motivational factors by Managers

“In UAE, evaluate the managers on whether they motivate their subordinates and how they perform afterwards”

Table 9. Motivational Factors by Managers.

Motivational factors for Workers

“Evaluate the workers in UAE whether they are motivated by their superiors or not and how they perform afterwards, and if they only consider money as the motivating factor”

Table 10. Motivational Factors by Project and Site Managers.

Incentive as motivation

“Investigating the incentives implemented in the UAE construction projects as a motivation for site employees”

Table 11. Incentive as Motivation Answer Options.

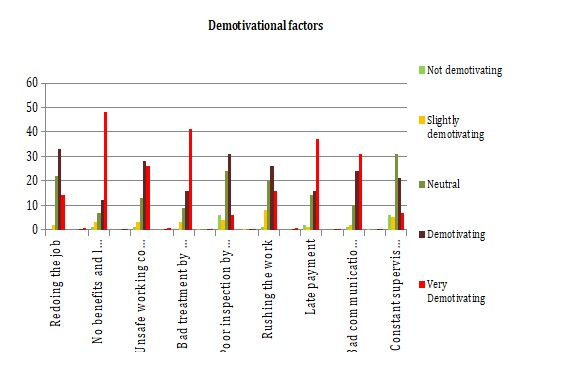

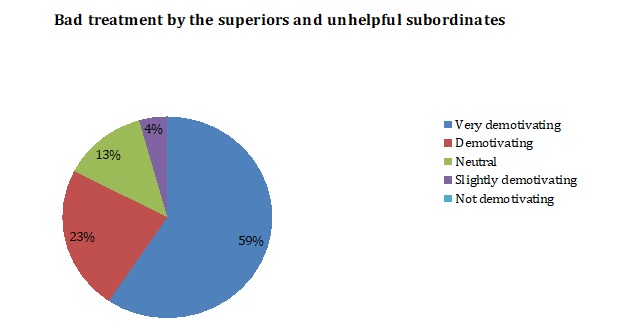

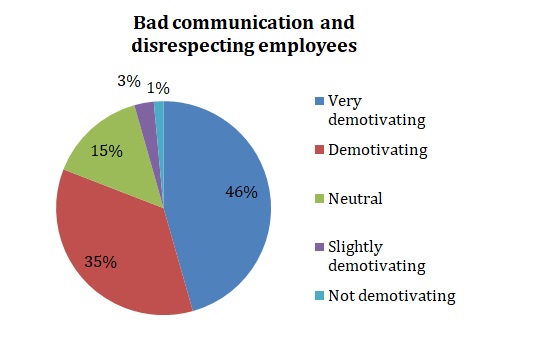

Demotivating factors

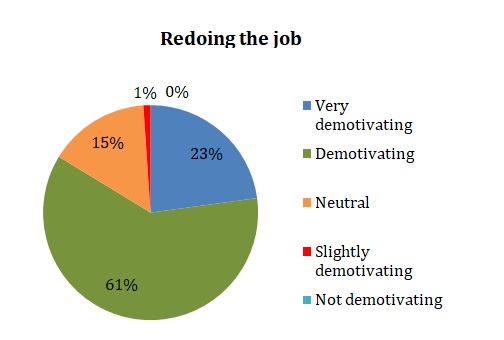

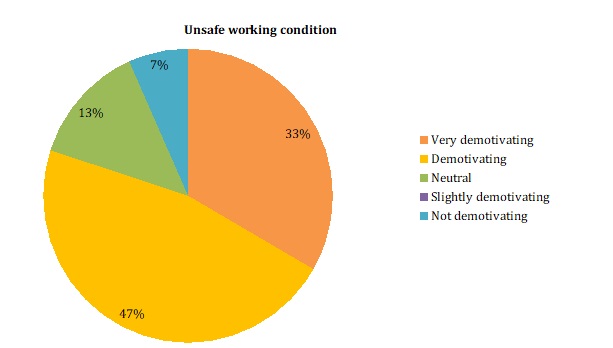

“Understanding the factors that demotivate the employees at site”

Table 12. Demotivating Factors Answer Options.

Comments/ opinions/ incidents/ other factors to motivate the employees and on how the employees perform better through motivating them/ lack of incentive programs (if any) used on site

Survey summary

The questions pertained to particular objectives which are related to the hypothesis and objectives of this paper, namely: the demographic profile, functions, and roles in the construction company, motivation and job satisfaction, motivational factors, the relation between motivation and performance, motivational factors by managers, motivational factors by project and site managers, incentive as motivation, demotivating factors, and suggestions and comments by workers and managers.

The first part of the questionnaire (Q1-Q4) is about the demographic profile of the participants, questions about age, years of experience in the construction industry, educational level or attainment, and occupation or function/responsibilities in the construction company they were working for. The next part (Q5) is about motivation and job satisfaction. Statements about motivation and perception of workers and managers about their job are plainly stated and the participants were asked to choose from a Likert scale, such as “strongly agree,” “agree,” “neutral,” “disagree,” or “strongly disagree”.

Q6 is about motivation factors and participants were asked what they perceived of the statements, whether the enumerated motivational factors were “very important,” “important,” “neutral,” “slightly not important,” and “not very important”. Question 7 (Objective 4) is about the relationship between motivation and performance wherein participants were again asked to rate the level of the statements from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.

Objective 5 (Q8) asked the participants about motivational factors commonly used in construction sites and participants were asked to rate the statements using the 5 Likert scales. In Q9, project and site managers were asked to rate the motivational factors. Q10 (incentive as motivation), participants were asked to choose which of the cited incentives were motivational. Q11 asked the participants’ rating on the demotivating factors. The last question asked the participants of their opinion and comments on how employees could perform better and what motivational factors could influence them to perform better in their job.

Survey Results and Analysis

Introduction

This chapter will provide all the results of the survey conducted on workers and managers in selected construction companies in the UAE. The term “workers and managers” refers to the four classifications of question 4 in the questionnaire. As the first two answer options will be considered as managers and the last two answer options will be considered as workers. This section will provide an analysis of the participants’ responses. This analysis will determine if there is a relationship between motivation and performance or whether motivated workers provide quality performance. The main aim of this dissertation is to determine the relationship between motivation and performance of managers and workers in construction companies in the UAE. Based on this analysis and assessment of the responses of the participants, conclusions and recommendations will be provided in the proceeding section of this paper.

Results summary for managers

Result summary for Q1 – Age

Table 1: Managers result summary for Q1.

Result summary for Q2 – Years of experience

Table 2: Managers result summary for Q2.

Result summary for Q3 – Education Level

Table 3: Managers results in summary for Q3.

Result Summary for Q4 – Occupation

Table 4: Managers results from summary for Q4.

Result Summary for Q5 – Motivation & Satisfaction

Table 5: Managers results from summary for Q5.

Result Summary for Q6 – Motivating factors

Table 6: Managers result summary for Q6.

Result Summary for Q7 – Performance of site employees

Table 7: Managers Result summary for Q7.

Result summary for Q8 – Managers motivating factors

Table 8: Managers result summary for Q8.

Result summary for Q9 – Motivating factors by workers

Table 9: Managers result summary for Q9.

Result Summary for Q10 – Incentives as a motivating factor

Table 10: Result summary for Q10.

Result summary for Q11 – Demotivating Factors

Table 11: Result Summary for Q11.

Result Summary for Q12

Please provide any further comments/ opinions/ incident/ other factors to motivate the employees/experience on how the employees perform better through motivating them/ lack of incentive programs (if any) used on your site.

Table 12: Result summary for Q12.

Results Analysis

Questions 1- 4

Figures 1 and 2 (with Table 1) are about the managers’ age demographic. Of the 21 participants classified as managers, 5 (23.8%) were aged 45 years old and above while 7 (33.3%) were 36-45 years old; 5 (23.8%) were 26-30 years old and 3 were 21-25 years old. The managers were relatively young and the age gaps were not too wide considering the hard work they encounter in the project site. There were 3 project managers and 2 constructio managers who were aged 45 years old and above and no project engineer, foreman, or workers who were of this age. The 45-year-old and above managers were the experienced ones. It can be said that this is necessary as they held managerial jobs that required a lot of responsibility, skill, and qualification that may affect the success of the project.

Figures 3 and 4 (with Table 2) are about years of experience in the industry. Six managers (28.6%) had 21 years and above experience in the construction industry, four had 16-20 years experience, while the rest had 10-15 years experience. This meant majority of the participants had many years of experience in the construction industry in various capacities. The project managers were experienced personnel, wherein 6 had 21 years and above experience; 4 had 16-20 years experience; 3 had 10-15 years experience, and 5 had 4-10 years experience. What drew the attention of this Researcher was the years of experience and the age, which were related; meaning, the more aged the manager the more he/she is experienced, skill and qualification very much needed in construction projects.

Figures 5 and 6 (with Table 3) are about educational attainment. Most of the managers (11) had Bachelor’s Degree, which could be an engineering degree or equivalent baccalaureate degree required by their respective company; 10 participants had a Master’s Degree. There was 1 who answered “other,” which in the opinion of this Researcher referred to a course qualification for office personnel. This Researcher learned that the Bachelor’s and Master’s Degrees were all related to construction work since it was a basic qualification for employees and managers/supervisors of construction companies in the UAE.

Figures 7 and 8 (with Table 4) are about the functions and responsibilities of the participants. There were 12 who were classified project managers or resident engineers and 9 Construction Manager/Assistant Resident Engineer/Project Coordinator, for a total of 21 managers. The comprised sample was classified as workers and managers in the survey. The first two classifications were considered managers while the second two classifications were workers. In other words, there were 21 managers and 75 workers, for a total of 96 participants.

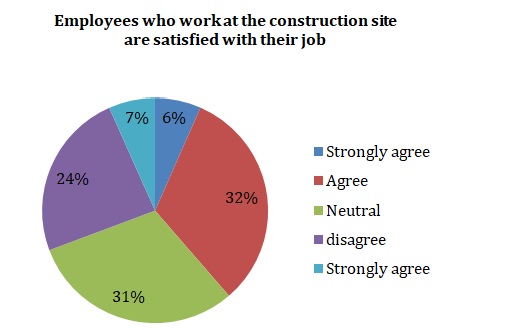

Figures 9 and Table 5 are about employees’ satisfaction, awareness of motivation in the UAE, and the relation between motivation and project success. The term used here is MA (e.g. MA1, MA2, etc.). Figure 10 is a pie chart for the first statement in the list of motivation awareness. Only 5 (26.32%) agreed and 1 strongly agreed that employees were satisfied with their job. 21.05% of the managers strongly disagreed but a large percent, 42.11% were neutral.

Figure 11 is for MA 2. The project managers strongly agreed and the construction managers agreed on the second statement that construction work is a demanding job. This is quite surprising considering that they held managerial jobs. Figure 12 is for motivation awareness 3. Two project managers strongly agreed and 5 project managers agreed that construction work was a demeaning job. There was a negative statement which the managers agreed and this is, ‘construction work is a demanding job and if given the opportunity would work in a different industry.’ For this statement, 7 managers strongly agreed and 6 agreed. In other words, a large number of managers agreed to this statement. This is understandable on the part of the managers since they had a big responsibility as managers. The majority of the managers valued motivation as important in the success of the project.

Again, this is quite surprising or significant. Managers should be the first to value their job and uphold it, encouraging and motivating workers to love their job.

Figure 13 is for MA 4 which dealt with the issue that that employees lacked respect among each other. Only 4 (10.53%) strongly agreed and 2 agreed which meant that not only a minority of the managers believed so but also they would like subordinates and fellow managers to respect each other. 26.32% disagreed and 26.32% strongly disagreed; meaning, they did not believe that employees lacked respect among each other.

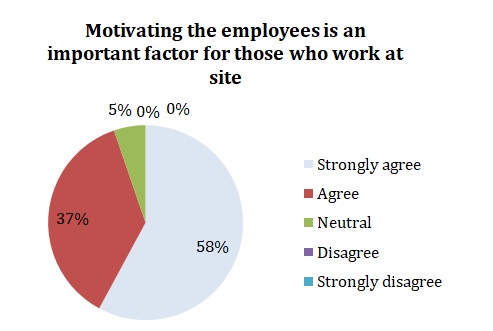

Figure 14 exhibits the fifth statement (MA5) which got a largely positive response from the managers, with 11 (57.89%) strongly agreed, 7 (36.84%) agreed, 1 neutral and no participant disagreed. The majority of the managers considered motivation as very important in the construction site.

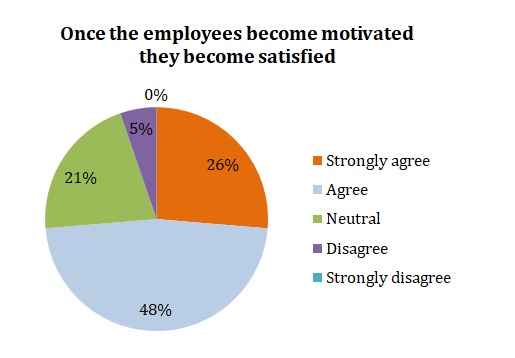

Figure 15 is about MA6, 5 (26.32%) strongly agreed and 9 (47.37%) project managers agreed. This is an example of the managers’ advocacy regarding motivation. The majority of them agreed in motivating employees to make them satisfied.

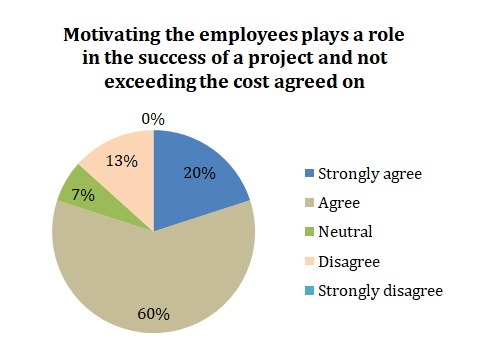

Figure 17 is for MA8 asking the managers to rate whether motivation affected the success of the project. Three project managers agreed and 9 (60%) construction managers agreed on MA8. Most managers had positive belief (opinion) about motivation. MA9 is on the issue of whether motivation benefited the project schedule or timely completion of the project. Nine (60%) of the construction managers agreed but 4 (26.67%) strongly agreed. There was a disagreement of 13.33% which is not quite significant.

Figure 19 is about MA10 asking the managers to rate the statement that motivation influenced the quality of the project. There was a large agreement from the construction managers, 9 (64.29%) strongly agreed and 4 (28.57%) project managers agreed, and there was only 1 who had a neutral position.

Figures 20 and 21 (with Table 6) are about motivating factors. The motivating factors have the same frequency for the managers; meaning there were 11 motivating factors mentioned and all had the same response count of 19. Although the two types of managers had varied opinions concerning the motivational factors, the gap was not too wide.

High salaries, extreme benefits, and rewards are important to managers. One project manager/resident engineer responded that it was “slightly not important” and another one responded that it was “not very important,” while the rest opted for “very important” or “important”. In the question about incentives, performance bonuses, and rewards, most participants answered that they were not a motivating factor.

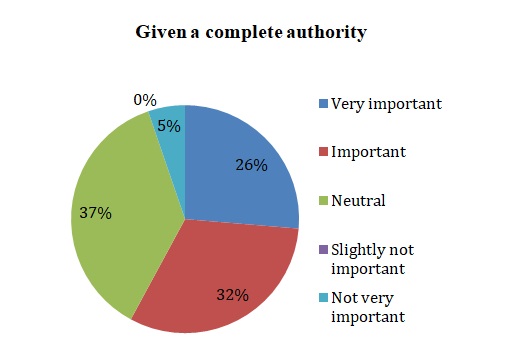

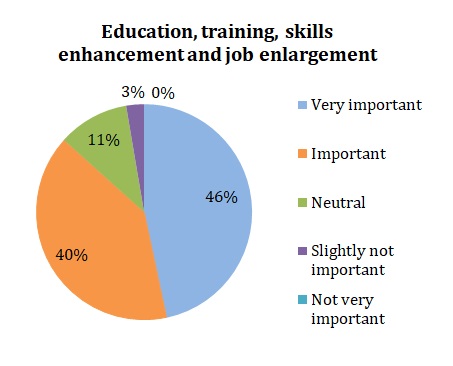

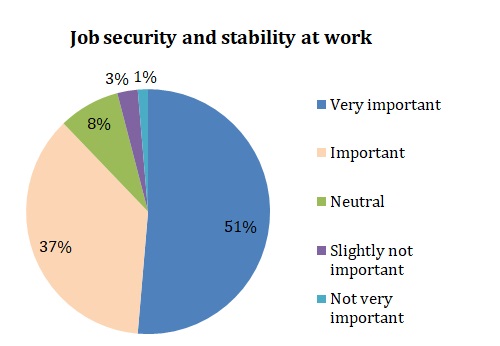

In Figure 21, the managers gave weight to acknowledging the work of subordinates (9 responses each); job security (14 responses); a friendly workplace environment (11 responses); high salaries, extreme benefits and rewards (12 responses); and education, training, skills enhancement and job enlargement (12 responses); and company policy to preserve employees’ rights (10).

In Figure 22 for Motivation 3, 9 (47.37%) project managers acknowledged that “flexible working conditions” were very important in their job, and 3 (26.32%) said that it was important in their job. However, 3 project managers and 2 construction managers considered this motivational factor as slightly not important and 1 project manager also responded that it was not very important. It also appears that a “healthy and safe working environment” (Figure 23) is very important and important to the managers. Only 1 project manager and 1 construction manager responded that it was not very important. Eight project engineers were neutral side.

While the managers favored high salaries and benefits, all the other motivational factors (self-enhancement, friendly workplace environment, recognition, etc.) are the most significant. In other words, the non-monetary overpowered the monetary motivational factors.

Figure 24 is for motivation 5. Nine project managers and 8 construction managers considered it very important and important, respectively, and there was 1 neutral. A good relationship was valued by the majority of the managers. On the other hand, Figure 25 dealt with recognition as motivation. Forty-seven percent of the managers considered it very important, and another equally large percentage also considered it important.

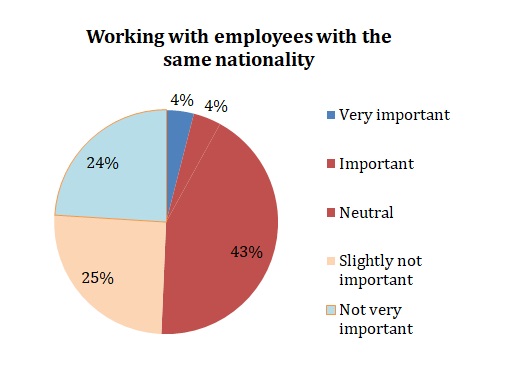

Figure 26 is about motivation 7 in which the managers 14 chose very important (76.38%) and 4 (21%) important. No one among the managers chose “slightly not important” or “not very important”. When it comes to Figure 9 for motivation 8, the majority had the opinion that working with employees of the same nationality did not matter, in which 32% said it was not very important and 16% said it was slightly not important.

Figure 28 is about motivation 8, in which 11(57.89%) of the managers said that a friendly workplace environment was very important and 5 (26.32%) said it was important. Nobody from the managers said it was not important, but 2 chose neutral which is quite not significant.

Figure 30 is for motivation 10 in which 10 (52.63%) of the managers said that it was very important and 5 (26.32%) said it was important. This meant that the majority of the managers valued employees’ rights.

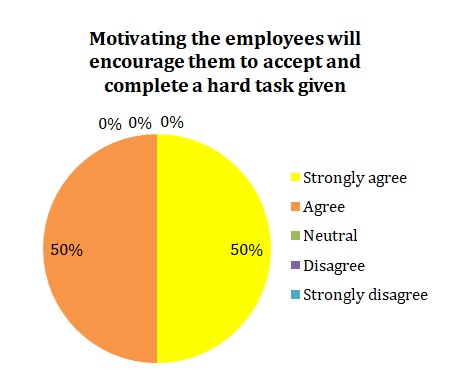

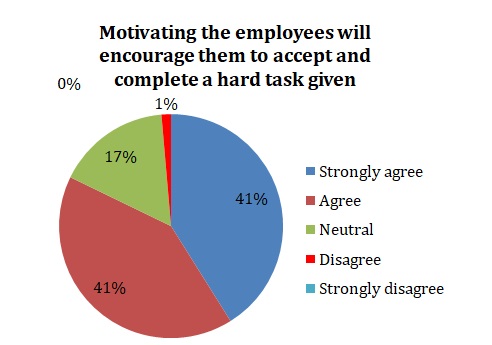

Figure 31 and Table 7 are about the relationship between motivation and performance. Figure 32 is about Performance 1 in which the managers agreed that motivation would lead to better performance, and this question earned 17 (52.94%) responses from the managers.